As an Actor, Terry Funk Made Action Stars Work

Terry Funk's particular genius for putting other wrestlers over made him a natural presence in action films, where he did the same for Stallone and Swayze.

Willow Catelyn Maclay is a freelance film critic who has written for outlets such as The Village Voice, MUBI, Roger Ebert.com, and Polygon. She is co-author of the upcoming book, Corpses, Fools and Monsters: An Examination of the Trans Film Image in Cinema. She also writes film criticism on her Patreon.

Being a wrestler and being an actor require very different things, but being a wrestler is sometimes better than being an actor in certain kinds of movies. Pro wrestlers like Jesse Ventura and Roddy Piper filled their roles in films like Predator and They Live with ample screen presence and charisma that was merely an extension of who they were as professional wrestlers, and these characters became pop culture phenomenon.

In the 1980s, genre filmmaking really took off alongside a perfect constellation of interest in body building, MTV-style editing, and the rise of the WWF. All of which doctored their presentation through the influence of montage as seen in Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky saga, which chronicled a narrative structure that prioritized shifting heel and babyface dynamics that unintentionally trained audiences to expect a professional wrestling equivalent from their movies about sports, action, and horror. Professional wrestlers naturally found their way into the movies during this decade, and one of the earliest adopters of this cross-over was Terry Funk, who worked frequently with Stallone dating back to Stallone’s 1978 directorial debut Paradise Alley.

Funk plays a monosyllabic goon named Franky the Thumper in Paradise Alley, and he is a constant thorn in the side for our heroes—the Carboni Brothers. Franky is a heavy for a local gang in the depression era Hell’s Kitchen, and he’s a money-making tough guy for an underground carnie wrestling organization. The Carboni Brothers are led by Cosmo (Stallone), a charming hustler who has concocted a plan to dominate the local territory, and make a lot of money in the process, by promoting his muscle-bound brother Victor (Lee Canilito) as the newest main event attraction “Kid Salami.”. Cosmo’s plan works, and in Stallone’s typically excellent usage of montage Salami goes through a series of wrestlers played by the likes of Ted DiBiase and Dory Funk in the quest to slay Franky the Thumper.

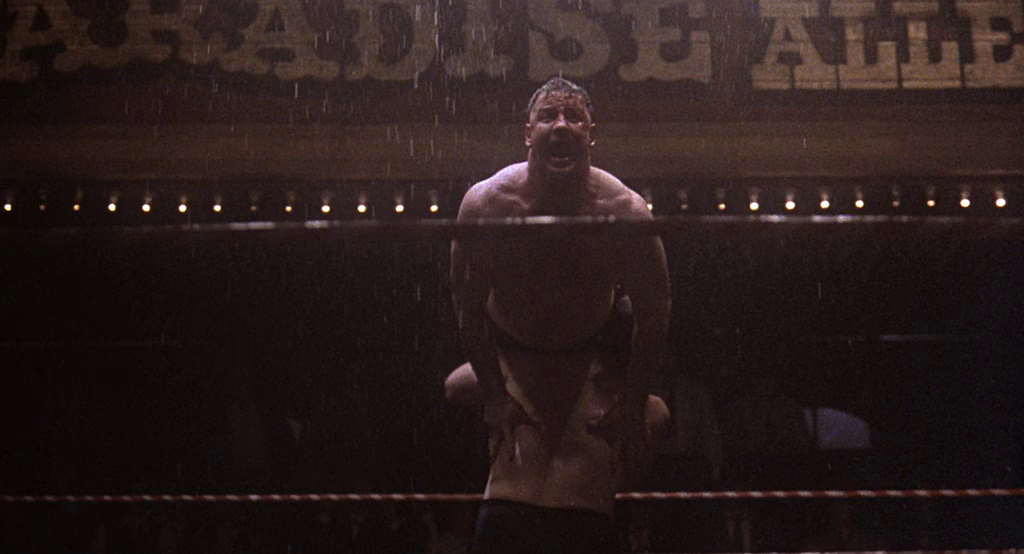

Terry could have easily played Franky as a variation on who he was as a professional wrestler at the time, but he opts to turn himself into the conventional idea of a big, foul- mouthed heel, worth taking down. He knows it is not his movie to steal, and he’s there to fall on his face and put Cosmo and his brothers over. It set a precedent for the types of roles he’d play as a guy who looked like an ass- kicker, but was there to get his ass kicked. There’s no ego about what Funk does as Franky, and this might’ve been why Stallone regularly brought Funk to other projects to choreograph fights, co-star in and perform stunts for the next fifteen years. Paradise Alley concludes on a beauty of a sequence from the great cinematographer László Kovács (Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces) that uses slow-motion photography to capture the sculptural qualities of pro wrestler bodies and movement. This sequence begins with Franky cutting a dazzling heel promo about ripping faces off, and ends with Terry Funk taking a backdrop onto a wrestling mat that is soaking wet from the leaking roof above, and in the middle of it all Funk never forgets to look like the embarrassed fool his character is, when he realizes he can’t beat Kid Salami, his life atop the card over.

Terry Funk stayed in touch with Stallone throughout the 1980s and collaborated on various projects including some stunt-work for the Rambo sequels, fight choreography in Rocky III and V, and a small role as a security guard in the arm-wrestling picture Over the Top. In Over the Top, Funk and Stallone share their only physical confrontation, which ends with Funk talking shit, and then immediately being thrown through a break-away door. Funk used what he understood about selling and pantomime to project whenever he did stunt-work, and he always went through objects a little harder than most when taking bumps in film. It’s there where his abilities as a wrestler proved worthwhile to action cinema.

This was never more clear than in his small, but scene-stealing role as Morgan in Road House. Funk plays the bouncer at the Double Deuce who is replaced by Dalton (played by Patrick Swayze at the peak of his powers). Dalton is like a new gunslinger who came into town. He’s a new alpha-male, and he scares Morgan. Swayze and Funk have real chemistry with one another, because Funk plays Morgan as an insecure tough guy in contrast to Swayze’s Dalton, whose Clint Eastwood-inflected quiet sureness renders him as a total opposite. This is once again where wrestling logic can influence the dynamics between characters, and it’s a little bit of a shame that Funk and Swayze never have a definitive blow-out fight. It does, however, make sense that Morgan would want to bring half a dozen other men to take on a single man. When Morgan does encounter Dalton for revenge he’s dispatched easily, and Funk throws his body through all sorts of furniture to make him look that much more of a buffonish heel.

Road House is a neo-western of a sort in the vein of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo or Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, but Terry Funk otherwise never appeared in a feature length Western of his own. The time for those movies had passed, even though it stands to reason he would have made his mark in that genre had those films been available. It’s easy to look at his career in wrestling promos and see the incidents where Westerns would have given Terry Funk a cinematic home. These include his promo leading up to a rematch with “Hot Stuff” Eddie Gilbert that feels like something out of Blazing Saddles. Any number of his promos in feuds with Ric Flair or Jerry Lawler, which used boisterous comedy to bold effect, feel not too far removed from the juvenile moments of comedic bit players in John Ford films. As a babyface Funk carried himself with a chivalrous effect that would have made him perfect for the genre.

There’s a quality to Terry Funk that is old and lost and not at all common among wrestlers or among actors, and this factor is probably why he was cast as Prometheus Jones in the short-lived Western television series “Wildside”. On this show Funk plays one of the five lawmen in the new town of Wildside, and he plays against type as a soft-hearted, gentle man who cares for animals. In the pilot episode there’s a lovely scene where he coddles a baby lamb and tells her he’ll be home soon after he and his gang go to rustle a Confederate Outlaw who is out in search of gold and killing anyone he comes in contact with. Funk feels at home in this setting, and in this role, while most of his co-stars feel like they are play-acting the idea of cattlemen or gunslingers. Terry Funk feels like he didn’t even need to act in this role, which was the trick in all of his performances in film or television. He knew what he could do, and he did it, and it never felt false.

Funk’s career in film and television occasionally bled over into wrestling, and most infamously during his feud with Ric Flair in 1989 when he was accused of going Hollywood and came back as a heel willing to say anything or do anything to his opponent. The feud that he had with Ric Flair contained some of his greatest moments as a performer, but my favorite instance of Funk’s abilities as an actor was with his exploding ring barbed wire death match for FMW with Atsushi Onita. It is an incredible match built upon the tension of whether or not they will or won’t they be tossed into the exploding barbed-wire, and whether or not they could escape the ring before it explodes.

Funk and Onita tear each other apart and fight alongside one another so valiantly that through their conflict they understand one another. It is an intimate experience built upon melodrama, and within the narrative of the match they have agreed to die for the sake of the contest. It concludes with one of the great babyface gestures from Onita as he runs back to Funk, who is lying there half-dead and covered in his own blood, and he wails open palm slaps on him numerous times to get him to wake up so he may avoid the blast, but he fails. Onita lays on top of him as the cage explodes in a slow-motion blast. There’s some lovely, cinematic camera work that follows of smoke billowing among the barbed-wire until the bodies of both competitors are revealed clinging to one another, and a wailing, somber guitar lick comes in, and it is a touch that wouldn’t be strange in a Michael Mann film. It’s so sincere that it goes beyond being cheesy, and into a very physical, genuine moment.

It makes sense that Funk would be involved in a match which was on the cutting edge of a new type of visual language in wrestling, because he was always around during the definitive moments of so many promotions throughout his illustrious career. Onita liked to stress that he was so serious about his commitment to pro wrestling that he would weep when cutting promos, and it is a natural evolution of Terry Funk with blood on his face, and tears in his eyes chanting “Forever!” to the Japanese audience after his first retirement match years earlier. It is perfect that these two men find each other in this moment of cataclysmic explosion, and then rebirth as they come to, and carry each other out of the ring.

Acting is not always about line delivery, or having the right accent, but about how you express yourself physically in any given moment, and when Terry Funk can barely stand, hobbling in the arms of Onita, he shows us something hard-won, blue-collar, heroic and caring about himself as a character, and as a man. When Funk gets to his feet and grazes his taped hands through Onita’s hair, he passes a torch. They are not enemies in this moment, but men bound by understanding in shared blood and experience. Funk says what he needs to say without actually saying it, and that is what acting is always trying to accomplish.